Guest post by Johanna Sköld, Karin Osvaldsson Cromdal and Klara Andersson. Child Studies Unit, Department of Thematic Studies and the Department of Social and Welfare Studies, Linköping University, Sweden.

E-mail: johanna.skold@liu.se

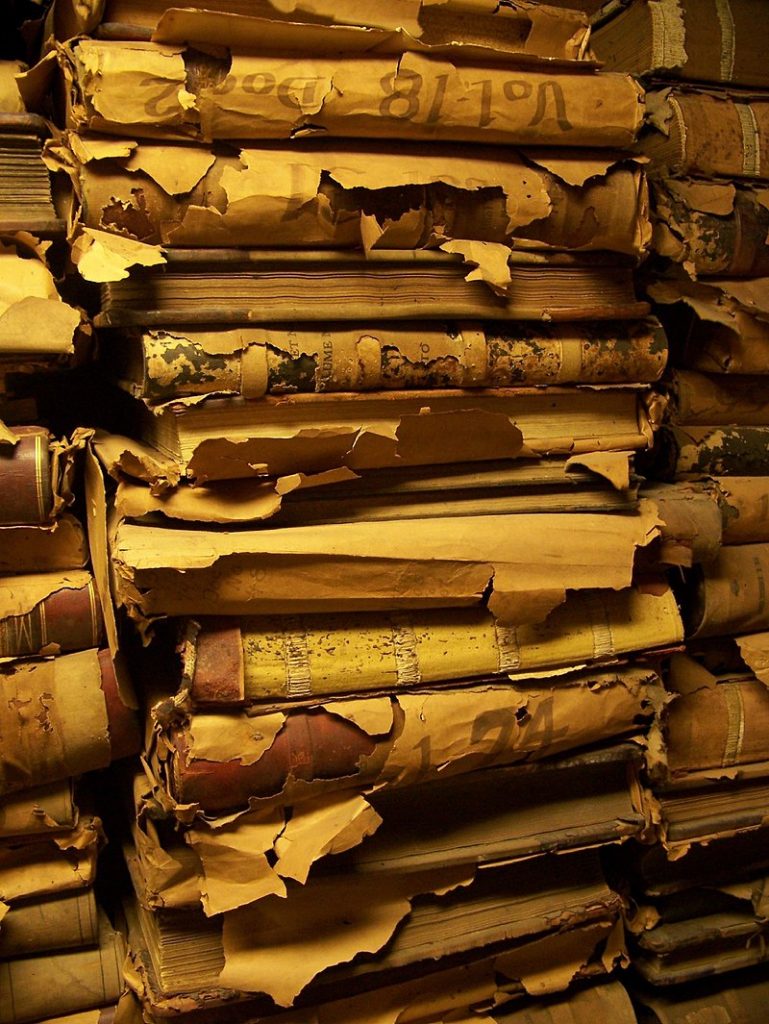

In her famous work Dust: Archive and the Cultural History (2001), Carolyn Steedman stated that “the Historian who goes to the Archive must always be an unintended reader, will always read that which was never intended for his or her eyes.” (Steedman 2001: 75). The fact that we are the unintended readers have ethical consequences, especially when the sources concern experiences of sensitive personal matters. In Sweden, when accumulating such sources from an archive, access will be regulated by rules enforced by law or by the archive.[1] In order to safeguard the integrity of the historical subjects the archive might allow restricted access to sources, for example by redacting any personal information in the data made available to the researcher. However, when using private collections that are not stored in an archive, no professional gatekeeper is present to safeguard the integrity of the historical subjects. Instead we must rely on our own ethical judgements. Moreover, in several countries, ethical vetting boards now also have to approve of research projects on sensitive matters that involve individual historical – though possibly still living – actors. But what if the historian’s ethical judgement conflicts with the ethical vetting board’s? What happens to historical research if we adjust our knowledge interests towards queries and sources ethical vetting boards are likely to approve? In this blog post we discuss two cases from Sweden where the Regional Ethical Vetting Board at Linköping University has evaluated two research projects, which have dealt with letters in private collections. The respective decision processes illustrate the dilemmas and problems that the process of ethical vetting might pose to historians.

According to the Swedish Ethical Review Act, any research that contains sensitive personal information about individuals must be approved by an Ethical Vetting Board (§ 3 SFS 2003:460), which in turn bases its decision on whether the risks the research poses for research subjects’ health, safety and personal integrity are outweighed by the research project’s scientific value (§ 9). If the research involves physical intervention, or if it is conducted by a method that either affects the individual physically or mentally, or entails an obvious risk of harming the individual physically or mentally, informed consent from the individual is required (§4, §16-22). The definition of sensitive personal information was given by the Personal Records Act (SFS 1988:204) until May 25 2018, then replaced by the European union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Both legislations define sensitive personal information as racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, membership of a trade union, health or a person’s sex life or sexual orientation.[2] Consequently, the introduction of GDPR did not change much for Swedish scholars in this regard. However, as the two case studies below show, it is important that historians are proactive and challenge the premises for what ethically sound research entails, as ethical regulations are rooted in medicine and not in the history discipline (Colnerud 2014).[3]

The first case – Children’s rights in society (BRIS)

Link to BRIS homepage

Our first case concerns letters from children to the Swedish child rights organization BRIS (Children’s rights in society). This organization was founded in 1971 as a reaction against cases of physical child abuse in Sweden. BRIS was involved in the drafting of the corporal punishment ban, enforced in 1979 as the first corporal punishment ban in the world. However, BRIS is more famous for its Kids’ helpline, which the organization established in 1980. Through the helpline (nowadays not only by phone, but also email and chat) BRIS has become an important channel for children’s voices. The organization also advocates children’s rights in the Swedish public. By cataloguing the issues children bring to the fore when they contact the helpline, BRIS has developed a system for representing children’s voices.

When we visited BRIS’ central office in 2016 looking for data for a research project, we came across a bunch of letters written by children in the 1970s and early 80s to one of BRIS’ founders – the famous children’s literature author Gunnel Linde. We quickly realized that this was an important finding: By these letters we would be able to identify what issues children themselves thought would be important for BRIS to be aware of before the Kids’ helpline was even established. Inasmuch as the letters may have concerned individual children’s problems and calls for help, the letters may also contain children’s views on what issues a child rights organization ought to engage in. As BRIS is an organization of adults working for children it is important from a child studies scholar point of view to critically discuss how children’s voices are represented.

BRIS has not donated their documents to any archive. All material is stored at the central office in Stockholm. By the first time we visited BRIS, the material was stored in the basement, together with old furniture and boxes of campaign material. Access to the letters demanded BRIS’ permission as well as their assistance to let us in in the storage room. However, access is also regulated by the ethical legislation we must follow as researchers.

The ethical regulations’ emphasis on informed consent poses challenges to historians. In our case the letters were written decades ago (40 years back), and they were often signed with the child’s first name only. In our application to the Regional Ethical Vetting Board we argued that while the letters may contain sensitive personal information, the probability of being able to identify any individual in the material was quite limited and informed consent therefore was a) not justified, and b) impossible to obtain. We stressed that we would not disclose any information that could be connected to any individual in our publications, and that we were interested in finding out which themes were mentioned in the letters – not in how individual children described their problems. However, the Regional Ethical Vetting Board was not persuaded by our arguments. They asked us to complement our application reflecting on the following questions:

The researchers should reflect on the risk that the now adult research subjects can suffer mental harm by knowing that their letters with sensitive issues have been studied by researchers, without their consent […] The researchers should reflect on how children’s and young people’s confidence in BRIS can be affected in the future if it becomes known that researchers have had access to children’s and young people’s letters without their consent, even if the letters are anonymized.

These remarks implied that informed consent was the only way forward. This was impossible for us – the letters did simply not contain enough information to identify each writer so we could contact them and ask if they were ok with us taking part of their letters. Moreover, had we been able to identify a couple of individuals and contacted them, we would have risked harming their integrity by disclosing that we knew that they had written letters to BRIS 40 years back. We thus found ourselves caught in a catch 22-situation.

The second question indicated that the Regional Ethical Vetting Board treated BRIS as research subject that required similar ethical considerations as research on any living human. If we got access to the letters, this might harm BRIS’ future reputation amongst children, the Ethical Vetting Board speculated. The fact that BRIS had given us access and that they were interested in our research was apparently irrelevant. Despite our efforts to clarify our ethical reflections around the issue, the Regional Ethical Vetting Board turned down our application for ethical approval arguing that “the scientific value of the research does not outweigh the risks that the project might entail for the research subjects’ health, safety and integrity” with reference to § 9 of the Ethical Review Act. Moreover, the Regional Vetting Board argued that no such research was allowed without informed consent from the research subjects.

If this reject decision had set precedence for the handling of historical letters with sensitive information, this would have endangered any future attempt by historians to access written records of past experiences in private collections. However, we appealed against the decision to the Central Ethical Vetting Board, and eventually got approval. The Central Board did not find that § 4 was applicable to our project, and therefore informed consent was not required. But by the time we received the approval, the project period was nearly up, and we did not have time to study the letters.

The second case – the children’s hotels

Our second case deals with letters that a journalist received after a radio broadcast about so-called children’s hotels (Sw barnpensionat) in the 1990s. This collection of letters, stored in the journalist’s home, were written by adults with childhood experiences of being sent away to such children’s hotels. For a research project in which we aim to investigate private out-of-home care arrangements, these letters contain very valuable information. The journalist had promised us access to the letters. However, as the letters may contain sensitive personal information about the authors, we sought ethical approval for this project as well – this time after the enforcement of GDPR in 2018. Once again, we argued that seeking informed consent from people who wrote these letters 20 years ago would not be possible due to incomplete information about full names, addresses etc. We also emphasized the risk of interfering with integrity if we contact people asking them for their consent to read their letters. Instead, we suggested that we would anonymize the letters before analyzing them. However, as the letters are stored in a private home, the anonymization cannot be carried out at site. The letters must be transferred to the university first. Moreover, since the anonymization will be conducted by us – the researchers – a total anonymization is not possible. If the letters had been stored in an archive, the anonymization would have been carried out by professional archivists before handling the data over to researchers. But private collections do not come with such facilities.

This time the Regional Ethical Vetting Board approved our application. It is of course satisfying that the vetting board found our argumentation sufficient to safeguard the ethical principles, but it is fascinating that similar ethical dilemmas (private collections of letters with sensitive personal information where informed consent is difficult to achieve) have been assessed quite differently by the same regional vetting board.

Is anonymization an ethical solution?

The ethical dilemmas historians face cannot be reduced to informed consent or anonymization (Vehkalahti 2016). In the second project where we adjusted our data collection towards anonymization in order to satisfy the principles that guide the Ethical Vetting Board, one might reasonably question whether anonymization is the most ethically accurate response. People who listened to the radio broadcast about the children’s hotels, and then wrote about their own experiences of having resided in such a place and sent it to a journalist may not have wished for anonymity. In fact, our experiences from addressing difficult life narratives in history have demonstrated that people often want to have their narratives acknowledged. By anonymizing the historical subjects, the archive our research project will create will be full of anonymous voices, not individuals. Those who devoted time to write down their narratives on which our research depends will never earn the credit they deserve.

So how can letters intended for someone else be used in research projects that require anonymization in order to address ethical principles, while at the same time creating another dilemma: that people’s personal narratives become stripped from everything that is personal? Or put differently: Researchers working with historical data need to be attentive to how ethical regulation created with medicine in focus, might result in new ethical dilemmas.

References:

Colnerud, G. (2014). “Ethical dilemmas in research in relation to ethical review: An empirical study” in Research Ethics, Vol. 10 Issue 4, 238-253.

Steedman, C. (2001). Dust. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Vehkalahti, K. (2016).

Dusting the archives of childhood: child welfare records as historical sources.

History of Education, 45(4), 430–445

[1] Access to official documents in state administrative archives is regulated by Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act (SFS 2009:400), and access to private archives stored in a public archive is , are regulated by agreements between the donor and the public archive.

[2] GDPR also include genetic data and biometric data ”that uniquely identifies a person” as sensitive personal information, see https://www.datainspektionen.se/other-lang/in-english/the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/sensitive-personal-data/ (accessed 20190401).

[3] It should be noted that since our two cases were evaluated, a new state authority – the so called Swedish Ethical Review Authority has replaced the regional Ethical Vetting Boards from January 1st 2019.